Learning to manipulate light from two or more locations in your home, like the top and bottom of a staircase or across a long hallway, immediately elevates your electrical DIY skills. But when you delve into Advanced 3-Way Switch Wiring Configurations, you're not just connecting wires; you're orchestrating a symphony of current paths. This guide is your backstage pass, giving you the expertise to tackle even the trickiest setups with confidence, safety, and a flicker-free outcome.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways for Mastering 3-Way Switches

- Safety First: Always kill power at the breaker and verify with a voltage tester before touching any wires.

- Common Terminal is Key: This is the pivot point for power, typically darker than the other terminals.

- Travelers are Messengers: These two wires (usually black and red in a 14-3 or 12-3 cable) ferry current between the two 3-way switches.

- Neutral Continuity: The white neutral wire must run continuously from the power source to the light fixture, bypassing all switches.

- Modern Code: Expect a neutral wire in every switch box, even if not immediately connected, for future smart device compatibility.

- Different Scenarios: Power can enter at the first switch, the light fixture, or even the second switch. Understanding the power entry point dictates your wiring strategy.

Before You Begin: The Uncompromising Rules of Electrical Safety

Electrical work isn't just about getting the lights on; it's about keeping everyone safe. Cutting corners here isn't just risky, it's potentially deadly. Heed these non-negotiable safety protocols:

- Kill the Power: Before you unscrew a single faceplate or touch a wire, locate the corresponding 15A or 20A circuit breaker in your main electrical panel and switch it OFF. If you're unsure which breaker it is, turn off the main breaker to the entire house.

- Verify Power Off: Do not trust your memory or the flip of a switch. Use a reliable Non-Contact Voltage Tester. Touch it to the switch itself, and then to each wire in the box after removing the faceplate. Confirm absolutely no voltage is present.

- Lockout/Tagout Lite: Tape a clear note over the circuit breaker you turned off, stating "DO NOT TURN ON - WORKING ON CIRCUIT." This prevents anyone from accidentally re-energizing the circuit while you're working.

- Proper Tools: Have insulated wire strippers, needle-nose pliers, screwdrivers, and a voltage tester on hand. Invest in quality tools; they're an extension of your safety.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): While not always strictly necessary for low-voltage residential work, safety glasses are always a good idea to protect against errant wire ends.

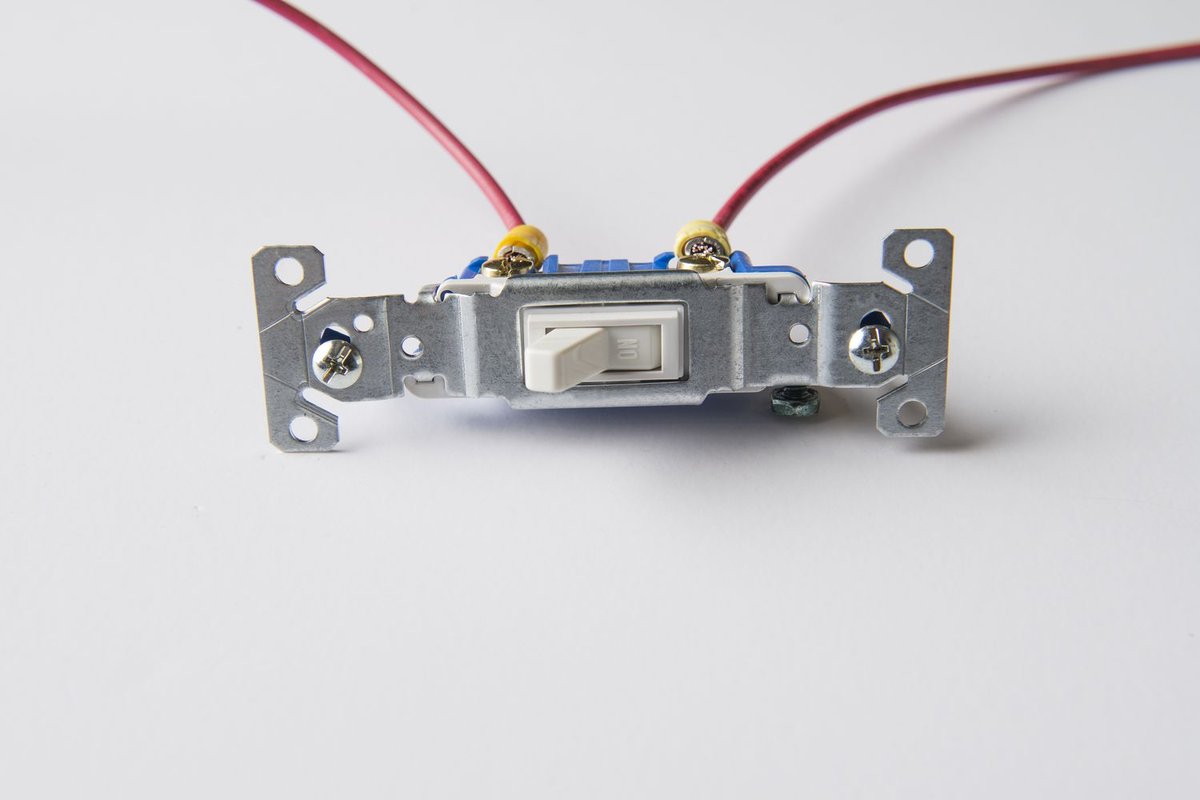

Deconstructing the 3-Way Switch: Your SPDT Navigator

Unlike a simple "ON/OFF" single-pole switch, a 3-way switch is a sophisticated internal mechanism designed to reroute power. You'll notice it lacks explicit "ON" or "OFF" labels because its position alone doesn't dictate the light's state; it always depends on the position of the other 3-way switch in the circuit.

At its core, a 3-way switch is a Single-Pole, Double-Throw (SPDT) device. This means it has one input (the "pole") that can be connected to one of two outputs (the "throws").

Let's break down its four key terminals:

- Common Terminal: This is the heart of the switch, the singular point where electrical current either enters from the power source or exits to the light fixture. It's typically distinguished by a darker color screw (often black or dark brass) to make it easily identifiable. Get this connection wrong, and nothing works.

- Traveler Terminals (1 & 2): These two terminals are the dynamic duo, responsible for routing power between the two 3-way switches. They're usually lighter bronze or copper-colored screws. The key is that current flows through one of these travelers, depending on the switch's internal position.

- Ground Terminal: A green-colored screw, this is your safety net. It connects to the bare copper ground wire, providing a path for fault current to safely dissipate, preventing shocks.

Think of it like a train track switch. The common terminal is the main line coming in or going out, and the two traveler terminals are two different tracks it can be routed to. When both switches are aligned to send the "train" (current) down the same set of tracks (traveler wires), the light illuminates. If they're on different tracks, the circuit is open, and the light stays off.

For a deeper dive into the fundamental principles, you can explore more about how to wire a 3-way switch.

The Unsung Heroes: Understanding Traveler Wires and Cable Requirements

Traveler wires are often misunderstood. They are not direct hot wires from the panel, nor are they neutrals. They are simply the pathways that carry the "signal" – the switched hot current – between the two 3-way switches.

- Color Conventions for Clarity: In standard residential wiring, the black and red wires within a multi-conductor cable are the designated travelers. If you ever encounter a white wire being used as a traveler (which can happen in older or less-than-ideal installations), it must be re-identified with black or red electrical tape at both ends to indicate it's not a neutral. This is a critical safety and code requirement.

- The Right Cable for the Job: To properly connect two 3-way switches and maintain neutral continuity, you'll need a specific type of cable:

- 14-3 NM Cable: (Black, Red, White insulated wires, plus bare ground). This is your go-to for 15-amp circuits.

- 12-3 NM Cable: (Black, Red, White insulated wires, plus bare ground). Use this for 20-amp circuits.

These "three-conductor" cables are essential because they provide the two traveler wires (black and red) and a continuous neutral wire (white) to meet modern code requirements.

Beyond the Basics: Unraveling Advanced 3-Way Wiring Scenarios

While the components remain consistent, the path power takes through your switches and light fixture can vary significantly. Understanding where your power enters the system is crucial for a successful and code-compliant installation. Let's look at the most common configurations:

Power Enters Switch 1, Then to Switch 2, Then to the Light (Modern Standard)

This is arguably the most common and straightforward configuration in modern wiring. Power (hot, neutral, ground) comes from the breaker panel directly into the first switch box. From there, a 14-3 (or 12-3) cable runs to the second switch box, carrying the two travelers and the neutral. Finally, a 14-2 (or 12-2) cable runs from the second switch box to the light fixture, carrying the switched hot and the continuous neutral.

- Key Advantage: All switch boxes have a neutral wire readily available, simplifying connections and ensuring compliance with current NEC mandates for smart switches.

- Wiring Nuance: The incoming hot connects to Switch 1's common. Travelers run between the two switches. Switch 2's common connects to the light's hot. Neutrals are spliced together and run continuously to the light.

Power Enters the Light Fixture First, Then Drops to the Switches (Older Homes)

Often seen in older installations, this setup has the incoming power cable (hot, neutral, ground) going directly to the ceiling light fixture box. From the light box, a single multi-conductor cable (often 14-3 or 12-3) drops down to the first switch, then potentially another to the second switch, or a single cable loops between them.

- Key Challenge: Identifying which wires are switched hot, constant hot, or neutrals can be confusing. A white wire might be used as a "switch leg" (a hot wire), making proper identification (with tape) absolutely critical.

- Wiring Nuance: The constant hot from the panel might connect to the fixture and travel down to the switches. The switched hot returns from the switch circuit to the fixture. This scenario often requires careful planning to ensure the neutral path is correctly maintained.

Power Enters Switch 1, Then to the Light Fixture, Then to Switch 2

In this configuration, power comes into the first switch box. From there, a multi-conductor cable (e.g., 14-3) carries the hot and travelers up to the light fixture box. From the light fixture box, another cable (again, often 14-3) carries the travelers and neutral back down to the second switch box.

- Key Advantage: Can be convenient if the light fixture is centrally located between the two switches, or if existing cable runs dictate this path.

- Wiring Nuance: The common wire from Switch 1 might travel to the light box, where it's spliced with the hot feeding the light, and then a separate set of travelers from the light box connect to Switch 2. This requires careful management of splices within the light fixture box.

Power Enters Switch 2 (Power at Far End), Then to Switch 1, Then to the Light

This scenario is essentially the reverse of the modern standard, where the power source is closer to the second switch in the chain. Power enters Switch Box 2, then a 14-3 (or 12-3) cable runs to Switch Box 1, and finally, a 14-2 (or 12-2) cable runs from Switch Box 1 to the light fixture.

- Key Advantage: Useful when the power source is more accessible at the "far end" of the run relative to the light.

- Wiring Nuance: The incoming hot connects to Switch 2's common. Travelers run between the two switches. Switch 1's common connects to the light's hot. Neutrals are spliced and run continuously to the light.

Each of these configurations is valid, but they demand a precise understanding of wire function and strict adherence to safety and code. Always map out your specific scenario before making any connections.

A Step-by-Step Guide: Power Entry at the First Switch (Scenario 1)

Let's walk through the installation process for the most common and code-friendly configuration: power entering Switch 1, traveling to Switch 2, and then to the light.

Materials You'll Need:

- Two 3-way switches (rated for your circuit, usually 15A or 20A)

- 14-2 NM-B cable (for 15A) or 12-2 NM-B cable (for 20A) for power in and load out

- 14-3 NM-B cable (for 15A) or 12-3 NM-B cable (for 20A) for connecting the two switches

- Wire nuts (various sizes)

- Electrical tape (black and red for wire identification)

- Ground pigtails (short lengths of bare copper wire) if multiple ground connections are needed in a box

- Light fixture

- Electrical boxes (deep single-gang boxes are recommended)

Tools for the Job: - Non-Contact Voltage Tester

- Wire strippers/cutters

- Needle-nose pliers

- Flathead and Phillips head screwdrivers

Step 1: Planning and Running Cables

Before you even think about stripping wires, plan your runs. This scenario requires three distinct cable segments:

- Segment A (Power In): Run a 14-2 (or 12-2) NM-B cable from your main breaker panel to Switch Box 1. Ensure enough slack in the box (6-8 inches beyond the box face).

- Segment B (Between Switches): Run a 14-3 (or 12-3) NM-B cable between Switch Box 1 and Switch Box 2. Again, leave ample slack.

- Segment C (Load Out): Run a 14-2 (or 12-2) NM-B cable from Switch Box 2 to your light fixture box.

Secure all cables to studs or joists with appropriate staples, typically within 12 inches of each electrical box and every 4.5 feet along the run. Ensure all cables are properly clamped into the electrical boxes.

Step 2: Preparing Wires for Connection

Carefully strip the outer jacket of each cable, leaving about 6-8 inches of individual insulated wires extending into the box. Then, strip approximately 3/4 inch of insulation from the end of each individual wire. Use needle-nose pliers to form a "J" hook on the end of each wire that will connect to a screw terminal, ensuring it wraps clockwise around the screw.

Step 3: Wiring Switch Box 1 (Power Entry)

This is where the hot wire from your panel makes its first appearance.

- Grounding: Gather all bare copper ground wires from all incoming cables. If your box is metal, add a pigtail from this bundle to the box itself. Then, connect another pigtail from this bundle to the green ground screw on your 3-way Switch 1. Secure all these connections with a wire nut.

- Incoming Hot: Take the black wire from the incoming 14-2 cable (from the breaker panel) and connect it to the Common terminal (the darker screw) on Switch 1. This is your constant power input.

- Neutral Continuity: Locate the white neutral wire from the incoming 14-2 cable and the white neutral wire from the outgoing 14-3 cable (to Switch 2). Splice these two white wires together using a wire nut. Crucially, do NOT connect any white wires to the 3-way switch. The neutral path must bypass the switch entirely and remain continuous.

- Travelers: Connect the black wire and the red wire from the 14-3 cable (going to Switch 2) to the two lighter-colored Traveler terminals on Switch 1. The order of these two traveler wires doesn't matter for functionality, but consistency in wiring practices is always good.

Step 4: Wiring Switch Box 2 (Light Connection)

This box connects the travelers to the light fixture.

- Grounding: Connect the bare copper ground wires from both the incoming 14-3 cable (from Switch 1) and the outgoing 14-2 cable (to the light fixture) to the green ground screw on Switch 2. Use a pigtail if connecting to a metal box as well.

- Travelers: Connect the black wire and the red wire from the incoming 14-3 cable (from Switch 1) to the two lighter-colored Traveler terminals on Switch 2. Match the orientation if you wish, but it's not strictly necessary.

- Switched Hot (Load Wire): Take the black wire from the outgoing 14-2 cable (going to the light fixture) and connect it to the Common terminal (the darker screw) on Switch 2. This wire will now carry the switched hot current to your light.

- Neutral Continuity: Splice the white neutral wire from the incoming 14-3 cable (from Switch 1) directly to the white neutral wire from the outgoing 14-2 cable (to the light fixture) using a wire nut. Again, the white neutral bypasses Switch 2 completely.

Step 5: Wiring the Light Fixture

The light fixture is the end of the line for the switched hot and the culmination of your continuous neutral path.

- Hot Connection: Connect the black wire (the switched hot coming from Switch 2's common) to the light fixture’s live (often black) terminal.

- Neutral Connection: Connect the white wire (the continuous neutral from your panel) to the light fixture’s neutral (often white or ribbed) terminal.

- Ground Connection: Connect the bare copper ground wire from the 14-2 cable to the light fixture’s ground terminal or mounting strap.

Step 6: Finalizing and Testing

- Secure Wires: Carefully fold all wires into their respective electrical boxes, pushing them gently in a "Z" pattern. Ensure no bare copper wire touches any hot terminal or ungrounded surface. Wrapping the perimeter of the switch (covering the screw terminals) with electrical tape before mounting is an excellent safety practice to prevent shorts.

- Mount Switches: Screw the switches securely into their boxes.

- Install Faceplates: Attach the decorative faceplates.

- Restore Power: Go back to your main breaker panel, remove your safety note, and flip the circuit breaker back to the ON position.

- Test Operation: Test the light from both switch locations. It should turn ON and OFF reliably from either switch, regardless of the other switch's position.

Tackling Common Snags: 3-Way Switch Troubleshooting

Even seasoned DIYers can hit a snag. Here are common issues and how to diagnose and fix them:

- Problem: The light only works from one switch, or it doesn't work at all from either switch.

- Diagnosis: This is almost always an incorrect connection of the common wire. A traveler wire might be connected to the common terminal, or the common wire itself is connected to a traveler terminal.

- Fix: Double-check your common terminal connections on both switches. Remember, the common is the darker screw. On the power-source switch, the incoming hot connects to the common. On the load-side switch, the wire going to the light connects to the common. The two travelers always go to the lighter-colored traveler terminals.

- Problem: The circuit breaker immediately trips when you restore power or when you push a switch into the box.

- Diagnosis: A "short to ground" or "short to hot" has occurred. This often happens if a bare ground wire or another wire accidentally touches a hot terminal or screw when you're pushing the switch into a crowded box.

- Fix: Kill the power immediately. Pull the switches back out. Carefully inspect all wires for pinched insulation or exposed copper making contact where it shouldn't. A great preventative measure is to wrap a few layers of electrical tape around the body of the switch, covering the screw terminals, before mounting it. This insulates them from the metal box or other wires.

- Problem: The light flickers, dims, or crackles, especially when operating a switch.

- Diagnosis: This indicates a loose connection somewhere in the circuit. A common culprit is "backstabbing" – using the push-in terminals on the back of cheaper switches instead of wrapping wires around the screw terminals.

- Fix: Kill the power. Remove any wires connected via backstabbing. Strip a fresh 3/4 inch of insulation, form a "J" hook, and securely wrap the wire clockwise around the side screw terminals, tightening them firmly. Also, check all wire nut connections for tightness.

- Problem: A white wire is identified as a traveler or hot, but it's not taped.

- Diagnosis: This is a code violation and a serious safety hazard, as someone might assume it's a neutral.

- Fix: Kill the power. If a white wire is used as a hot or a traveler, it must be re-identified with black or red electrical tape at both ends to indicate its true function. Use black tape for switched hot, red for traveler.

- Problem: The light doesn't work, and you confirm power at the first switch, but not the light. You suspect the neutral.

- Diagnosis: The neutral wire path from the panel to the light fixture might be interrupted.

- Fix: Remember, the neutral wire must never connect to a switch. It must run continuously from the power source, through all switch boxes (spliced together with wire nuts), directly to the light fixture's neutral terminal. Trace this path carefully to ensure continuity.

- Problem: You only ran 14-2 (or 12-2) cable between the two switches.

- Diagnosis: You've used the wrong cable type. A 14-2 only provides one hot, one neutral, and a ground. You need two traveler wires and a neutral (plus ground) between 3-way switches.

- Fix: There's no workaround; you'll need to replace the 14-2 cable with a proper 14-3 (or 12-3) NM cable to provide the necessary conductors.

Staying Safe & Compliant: The National Electrical Code (NEC) Mandates

Electrical codes exist for a reason: safety. Ignoring them isn't just illegal; it puts lives and property at risk.

- Proper Grounding: Every switch, metal box, and fixture must be properly grounded back to the service panel. This provides a critical safety path in case of a fault.

- Wire Gauge & Circuit Rating: Always match your wire gauge (e.g., 14-gauge for 15-amp circuits, 12-gauge for 20-amp circuits) and switch ratings to the circuit breaker amperage. Overloading a wire can cause overheating and fire.

- Neutral Wires at Switch Locations: Modern NEC (since 2011) generally requires a neutral wire to be present in every switch box. Even if your traditional 3-way setup doesn't immediately use the neutral in the switch box (it merely passes through), its presence is vital for future compatibility with smart switches, dimmers, and other IoT devices that require a neutral connection for power.

- Traveler Wire Identification: As mentioned, black and red are standard for travelers. If a white wire must be repurposed as a hot or traveler, it must be re-identified with black or red electrical tape at both ends.

- Box Volume (Box Fill): Electrical boxes have a maximum capacity for wires. Overcrowding leads to heat buildup and fire risk. A standard 14-gauge circuit with a 3-way switch and two cables entering the box might easily exceed the volume of a shallow single-gang box. Always opt for "deep" single-gang boxes (typically 20-22 cubic inches or more) to ensure adequate space for wires and splices.

Clarifying the Jargon: 3-Way vs. 4-Way & Other Terms

The world of electrical switches can be confusing with similar-sounding terms. Let's clear the air:

- 3-Way Switch: This is what we've been discussing. It has three main terminals (one common, two travelers) plus a ground. It's an SPDT (Single-Pole, Double-Throw) mechanism. Used for controlling a light from two locations.

- 4-Way Switch: Significantly different, a 4-way switch has four main terminals (two travelers in, two travelers out) plus a ground. It's a DPDT (Double-Pole, Double-Throw) mechanism. It's never used by itself; it's always installed between two 3-way switches to enable control from three or more locations. For example, a long hallway might have a 3-way switch at each end and one or more 4-way switches in the middle.

- Double Pole Switch: Not to be confused with a 3-way switch. A double pole switch is typically used for 240V appliances (like water heaters or motors) and has four brass terminals, allowing it to switch two separate hot wires simultaneously. It's not for controlling lights from multiple locations.

- Combo Switch / Stack Switch: These devices combine two separate single-pole switches (or a switch and an outlet) into a single device body, designed to fit in a standard single-gang box. They operate as independent circuits and are not related to 3-way systems.

- "2-Way Switch" (UK/Europe): If you're consulting international resources, be aware that what Americans call a "3-Way Switch," Europeans and those in the UK often refer to as a "2-Way Switch." They accomplish the exact same function of controlling a light from two locations.

Practical Applications: Where 3-Way Switches Shine

Knowing how to wire advanced 3-way configurations isn't just theoretical; it opens up a world of practical convenience in your home:

- Stairway Lighting: Control the light from both the top and bottom of a staircase, eliminating fumbling in the dark.

- Hallway Lighting: Turn on the lights when you enter a long hallway and switch them off at the other end.

- Master Bedroom Suites: Control your bedroom's main light from the entrance and a bedside location, or even from an ensuite bathroom entrance.

- Garage & Basement Access: Illuminate a garage or basement from inside the house and from within the space itself.

- Large Rooms with Multiple Entry Points: Control overhead lighting in a spacious living room or open-concept area from different doorways.

Mastering Your Home's Electrical Symphony

Understanding Advanced 3-Way Switch Wiring Configurations is more than just a technical skill; it's about taking control of your living space, enhancing convenience, and doing so with unwavering confidence in safety and code compliance. While the initial setup might seem daunting, breaking it down into manageable steps, understanding the role of each wire and terminal, and always prioritizing safety will lead to a successful, well-lit outcome. Remember, the journey from basic switch replacement to mastering complex wiring is incremental, and each successful project builds your expertise. So, grab your voltage tester, study your diagrams, and confidently embark on your next electrical upgrade!